- Home

- Clifton Adams

The Long Vendetta

The Long Vendetta Read online

The Long Vendetta

Clifton Adams

* * *

The Long Vendetta

Jonathan Gant

This page formatted 2005 Blackmask Online.

http://www.blackmask.com

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

* * *

Buck Coyle couldn't ride himself of the feeling that that accident that had landed him in the hospital hadn't been an accident at all, but a deliberate attempt to murder him. So far as he knew, he didn't have an enemy in the world. Why would anyone try to kill him?

It was gruff Police Lieutenant Garnett who connected the murders of the two other men with the attempt on Coyle's life—but even then it didn't make sense. Many years before, Coyle—three-stripe Sergeant Coyle then—had commanded a tank which had destroyed a stone cottage in Germany, in which a woman and a small child were killed. And the two murdered men—Orlan Koesler and Charlie Roach—had been members of his tank crew.

That small stone farmhouse had with its thatched roof and stone shed had been the horrible focus of many nightmares for Buck Coyle through the years—that and the sight of a woman's shattered body and a lifeless blonde little girl who looked like a small, cast-aside doll.

Was it possible that the woman's husband could have come to America to avenge their deaths? It would have been a simple matter for the man to trace them. But why should he have waited all these years? A long vendetta, a long time to brood over the death of his family, the destruction of his home...

CHAPTER ONE

It seemed like a nice place, as hospital rooms go. Green-tinted walls, cream ceiling, a nice view of the city. On one side of the bed, there was a telephone and a chrome-plated valve for the piped-in oxygen; on the other side, a remote control unit for the built-in television. It smelled like money. About thirty bucks a day, not counting pills and doctors— which was a long way out of my class. I looked around, found the panic button and jabbed it.

Vague impressions and fears moved uncertainly in my brain. What was I doing in a hospital? My tongue was thick; my mouth was dry. My head ached and my eyes didn't want to focus.

Beginning with my head, I checked myself out. The left side of my face was bruised and sore, but nothing seemed to be broken. My arms were all right, except for more bruises. There was a good deal of skin missing from my right hip, thigh, knee, and ankle.

The last thing I remembered was driving away from the ship in Allan Ditmire's Bentley convertible. Driving through Plains City on a fine autumn day, with nothing on my mind more serious than wondering where to take Jeanie Kelly for dinner that night. Floating along in that beautiful, handmade hunk of precision automobile, with not a worry in my head.

And there the scene stopped.

Suddenly I had a worry. It sagged in my stomach like a shot-put.I must have wrecked the Bentley! That would explain the break in my memory. It would explain my waking up in a hospital. Almost twenty thousand dollars' worth of automobile—now there was a worry a man could get his teeth into.

I waited for the nurse, wondering what had happened to my clothes. Then the door whispered open and in stepped not a nurse, not a doctor, not even a scrubwoman, but a lieutenant in the Plains City Police Department by the name of Garnett. Woody Garnett.

I didn't know his name then, of course. I didn't even know he was a cop. He was a big, bald, sweaty, dead-panned bull of a man wearing a wrinkled gray suit and a wilted shirt and a tie that was just something he had around his neck. In his mouth, clinched between strong yellow teeth, was a bulldog briar. He came into the room, walking as though his feet hurt, studying me bleakly from under a set of wildly bushy eyebrows.

He sank wearily into a groaning chair near the television. From his coat pocket he took a dime notebook and consulted it. “Charles Elwood 'Buck' Coyle?” he asked.

I nodded. “We know who I am. Now who are you?”

“You own a garage and body shop on North Harrison, specialize in imported cars and road racers. You live at the Westerner Apartments, on Santee. No parents, no known relatives...”

I said, “If you're checking my credit, you can forget it. I'm getting out of this place as soon as somebody brings my pants.”

He closed his notebook and studied me with vague interest. “I'm not checking your credit, Mr. Coyle. My name's Garnett. Lieutenant, City Police, Homicide.”

My stomach hit bottom. Now I knew what real worrying could be. “Homicide...” I had to clear my throat. “Was... someone killed?”

“How do you mean?”

“The accident,” I heard myself saying. “There was an accident; I don't even know how it happened, but I can't believe that I killed...”

“What makes you think there was an accident?”

It was my turn to blink. “The last thing I remember I was driving the Bentley. The shop had given it a five-thousand-mile shakedown and I was driving it back to Allan Ditmire, the owner. Now I wake up in a hospital. It's the only thing that figures; there had to be an accident. That's why you're here, isn't it?”

Garnett tamped his pipe with his thumb. “Think hard, Mr. Coyle. What is the very last thing you remember?”

I tried so hard that sweat beaded on my forehead. But all I could think of was that I had hit and killed someone. “I'm sorry, Lieutenant, but that's the last I remember. I was taking the Bentley to the Mayhew Building—that's where Mr. Ditmire has his offices— I was just driving...” Then, slowly, a small window in my mind began to open. “... Wait a minute. Iwasn't driving. I'd already reached the Mayhew Building, and was just sliding out from under the wheel...”

I began to breathe again. How could there have been an accident if I had already parked the Bentley? How could I have killed anyone?

Lieutenant Garnett rubbed his chin thoughtfully. “You've kind of got it turned around, Mr. Coyle. You didn't kill anyone. And there was no accident. Someone tried to kill you.”

I heard the words, but it took the meaning a long time to sink in. The lieutenant was saying that someone had tried to murder me. Me, Buck Coyle. Not a name in a newspaper, not a character in television or in a book, but me.

“So that's what I'm doing in a hospital,” I said, my voice sounding thin and faraway. “But why?”

Garnett shrugged. “I was hoping you could tell me.”

I shook my head, still unable to digest the whole of the ugly meaning. “You must know your business, Lieutenant, but this time you have to be mistaken. I don't have any enemies, except in a business sort of way, and none of them have the guts for murder.”

The lieutenant rubbed his pipe bowl alongside his nose, polishing the dark briar until it shone like a black pearl.

“All right,” I said wearily. “If you can't tell me why, tell me how.”

Garnett consulted his notebook once more. “Yesterday, like you say, you left your shop in the Bentley. That was around four in the afternoon. Around four-twenty you parked the Bentley in front of the May-hew Building. You got out on the driver's side, walked around in front of the car, and the Ford tried to cut you down. You had your back to the Ford, so it figures that you wouldn't remember that part of it. But it couldn't have been an accident; the driver of the Ford had to cut sharply in front of the Bentley to hit you. Even so, he clipped the Bentley's front fender, lost control for an instant, which was just long , enough to save your life. Instead of hitting you head-on, he sideswiped you and sent you sprawling on the sidewalk.”

; I felt strangely hollow. Garnett sat back and gazed at the ceiling. “No sir, Mr. Coyle, it was no accident. That gent was out to kill you, all right. He ditched the Ford a few blocks from the scene—it was on our pickup list. The killer stole it just for the job, and had his own car waiting to make his get-away in.”

I was thinking:Yesterday around four o'clock. Here it was nineteen hours later, in the middle of the next day. I said, “How about witnesses?”

“At least a dozen. None of them got a good look at the driver, but the general impression is that he's in his late twenties, dark hair, a neat dresser. You getting any ideas, Mr. Coyle?”

I shook my head.

“You ever hear of a fellow named Marvin Storch?”

I closed my eyes and tried to remember. The name meant nothing.

Garnett shrugged. “Storch is a newcomer in what is almost an extinct business. He's a professional assassin. Getting evidence to convict with is a tough thing, but we do know that hit-and-run is Marvin's favorite game. And he's good. Far as we know, you're the first mistake he's made—if this was actually his work.”

I felt sick. A professional killer in Plains City? A hired assassin, gunning for me? Somebody was crazy, and I was beginning to suspect that it was a police lieutenant named Garnett.

He smiled faintly. “I know this is a lot to throw at you all at once, Mr. Coyle. Maybe I'm on the wrong track about Storch.”

“You're very much on the wrong track, Lieutenant. The worst enemies I ever made are a few race drivers who got squeezed out on tight curves, and if any of them wanted to kill me he'd do it on a track. How much does a professional killer cost, anyway? A thousand dollars? Five thousand? My life simply isn't worth that kind of money to anybody but me. That driver was probably a kid who hoisted the Ford for kicks; then he lost control for a moment and panicked...”

The lieutenant gazed vacantly about the room, then suddenly changed directions.

“Have you received any unusual mail, Mr. Coyle? In the past day or so?”

“What has my mail got to do with hit-and-run?”

There was a certain steeliness in his voice as he said: “Will you answer the question, please?”

“I'm not sure what you mean by unusual. I get all kinds of mail, like anybody else, but there have been no threatening letters. If that's what you mean.”

Garnett sighed. “That's what I meant. Well, thank you for your co-operation. Probably you're right and there's not a thing to worry about.” He smiled widely, without taking his pipe from between his teeth, nodded and shambled off toward the door.

“By the way,” he said, pausing in the doorway, “You don't happen to know a fellow named Koesler, do you? Orlan Koesler?”

A vague, uneasy warning blinked in the back of my mind. For just a moment it seemed that I was on the brink of remembering something. A face. A name. Something...

But I shook my head. “No. The name means nothing.”

“What about Roach?” he asked. “Charlie Roach?”

Again, I shook my head. “Just a name, Lieutenant. I don't know anyone named Charlie Roach.”

Garnett ignited a kitchen match with his thumbnail. Puffing on his pipe, he watched me through a rising cloud of bluish smoke. Then he turned again and was gone.

I lay there for what seemed a long while, carefully steering my thoughts away from some unseen ugliness that I couldn't even give name to. Two student nurses floated in on crepe-soled clouds and changed the bed with incredible efficiency. A doctor came in, chatted pleasantly and reminded me how lucky I was not to have been killed. He looked at my chart and said they wanted to keep me another day to make sure there were no internal injuries. I didn't even argue. I was too busy trying to think what it was that Garnett had started with the mention of those two names, Roach and Koesler.

The worst thing about hospitals is that they give you too much time for thinking. Now I thought of Mary. And the marriage that we had had. The good and bad of it. And the violent blackness that had crashed down around me when she had died.

It had been months since I had thought of Mary that way, freely. I could almost see her—small, bright, resilient as spring steel, her short hair flying, her eyes brilliant with laughter, drifting her blood-red Jag into some hellish hairpin corner at suicidal speeds. And that, rightly enough, I suppose, had been the way she had died. Exactly what had happened we never knew. The experts guessed faulty brakes. More likely, Mary had started shifting down an instant too late, gambling to gain that last precious fraction of a second on the straightaway.

Gambling with her life. And losing. I could still hear the crowd's screaming. I could see the sleek Jaguar leaving the road in a crazy, side-slipping horror, and the crash into the hay bales. And the explosion, bright and fiery.

All that was left of the Jag were senseless chunks of metal. Of Mary, only a name and a memory. And a long, dull ache.

That had been just a year ago, almost to the day. Or a dozen lifetimes. Time is a relative thing and it is hard to remember.

But it was good to know that I could think of Mary now without losing myself in hopelessness. It was good to be able to think of another girl, like Jeanie Kelly, without having an unreasonable guilt come down on me like a smothering hood. I was grateful to Garnett, whose questions had started me thinking. I could almost be grateful to the driver of that Ford who had put me here—but not quite.

A smiling, starched, and rustling nurse came in, took my temperature and gave me a pill. I lay for a while staring at the ceiling. I went to sleep.

Jeanie Kelly used her lunch hour to bring me my mail, a basket of fruit from the garage help, and the latest sports car magazines from herself.

Her grin had the false brightness of one that had just been turned on. “Hi,” she said, handing me a damp washcloth. “The nurse said give you this. They're bringing you some lunch.”

“You delivering for the produce man today?”

She looked at the basket of fruit and laughed. Jeanie was tall, quiet, mature in mind and body. Jeanie was a sense of peace after Mary's storm and lightning. A psychologist could probably build something of that, but Jeanie in no way took Mary's place in my life. She had quietly and surely made her own place.

Now she shook her head, grinning that grin which was not quite real. “I still can't believe it. All your years on the tracks, behind the wheels of everything from M.G.'s to Maseratis, and you let a car hit you on a downtown street.” She looked at my face, which was getting more discolored by the minute. Then she turned and walked to the window, looking out at the city.

“I had a visitor this morning,” she said. “A police lieutenant, Garnett.”

At first, I felt anger. If Garnett wanted to try his screwball theories on me, that was one thing, but when he started worrying Jeanie, that was playing a hunch too hard.

“Don't pay any attention to the lieutenant. He likes to be dramatic; maybe he's been reading too many crime comics.”

I looked at her. She was a beautiful woman in her own quiet, almost regal way. The kind of woman a man enjoys being seen with. Bright and young, but not so young as to remind him that he is beginning to crowd forty. She was a highly efficient girl Friday to a Plains City insurance executive; she wore clothes like aVogue model and appreciated fast cars, but not to the point of being a nut on the subject. I meant to marry her as soon as I got the nerve to ask her, if she would have me.

She said, “Does someone want to kill you, Buck?”

“Some of my creditors, maybe. And Allan Ditmire, after what happened to his Bentley. By the way, have the insurance boys been notified?”

She nodded, still not turning from the window. “I took care of it myself. Buck, I know it sounds crazy, but I think the lieutenant's worried.”

“Garnett's got an over-active imagination. The lieutenant's assassin will turn out to be just another punk kid who never learned how to drive. I'll be out of this place tomorrow and I want everybody in a celebrating mood.”

Now

she turned from the window, smiling. “All right, Buck. Whatever you say.”

A nurse came in with my lunch.

“Steak, green beans, Waldorf salad; pretty high living for a greaseball. How did I land in a place like this, anyway?”

“Nothing but the best,” she laughed, “for the man who drives a Bentley convertible.”

When Jeanie left, the room was suddenly impersonal and cold. The steak, which was sure to cost me plenty, was tasteless in my mouth. I pushed the lunch away and thumbed through the mail.

There was one item that was foreign, out of place, and somehow ugly in that pile of precise commercial correspondence. It was a dime-store envelope with my name and shop address scrawled in pencil. I turned it over, but there was no return address. There was no cause for it, but my palms were suddenly sweaty as I ripped the envelope open and unfolded the single sheet of paper.

There the same penciled, cramped back-handed scrawl had formed the misshapen words:

Now you must pay for those you murdered in Ubach.

I stared for a long time at those hunched, deformed words. In my mind a long-sealed door swung slowly open, and an old recurring nightmare moved into the shocking light of consciousness. It had been a long while, weeks and months, since this particular nightmare had come to haunt me, and I had thought and hoped that this one page in the history of Buck Coyle could be forgotten.

Now this.

I looked at my hands and they were shaking. I couldn't stop them from shaking. And the thing that had been so neatly sealed away all came rushing back.

In the dream, it is always October. Our tanks are deployed on the plains of Ubach, in that gray surrealistic world of abrupt slag mountains, and concrete dragons' teeth, tank traps, pillboxes. And corpses. Plenty of corpses of machines and men. And fires. No matter in what direction you might look, you could always see a tank, or a house, or a town, or something, slowly burning.

That is the setting of the dream. Germany. Somewhere to the east of Ubach, between Ubach and Julich, and north of Aachen, and a little to the west of the River Wurm. That is where we always are, the four of us, with our light tank dug into that hard, worn-out German earth, with our 37 mm turret gun and a dismounted light machine gun pointed toward the Rhine. And there we waited, the four of us, pinned down for three miserable days by observed fire from some Kraut artillery school. Just kids, the story had it. Tough towheaded teen-agers, bucking for commands in the SS.

The Long Vendetta

The Long Vendetta The Law of the Trigger

The Law of the Trigger Whom Gods Destroy

Whom Gods Destroy Never Say No To A Killer

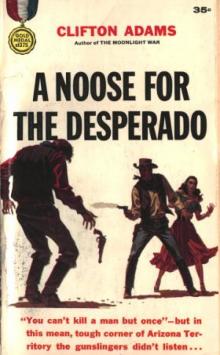

Never Say No To A Killer A Noose for the Desperado

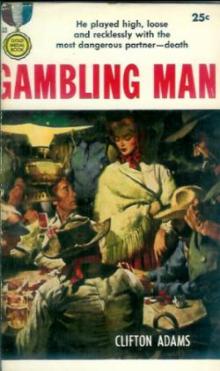

A Noose for the Desperado Gambling Man

Gambling Man The Last Days of Wolf Garnett

The Last Days of Wolf Garnett The Desperado

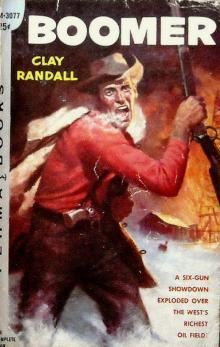

The Desperado Boomer

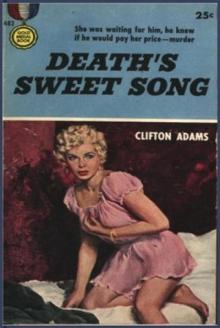

Boomer Death's Sweet Song

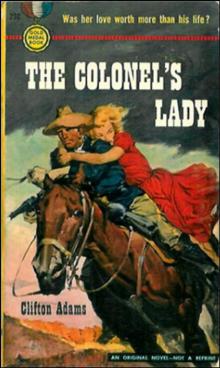

Death's Sweet Song The Colonel's Lady

The Colonel's Lady