- Home

- Clifton Adams

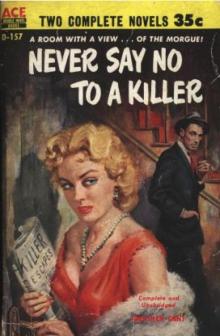

Never Say No To A Killer

Never Say No To A Killer Read online

Never Say No To A Killer

Clifton Adams

A Room with a View... of the Morgue!

Never Say No To A Killer

Clifton Adams

A Room with a View... of the Morgue!

Copyright 1956, by A. A. Wyn, Inc. All Rights Reserved

CHAPTER ONE

THE ROCK WAS about the size of a man's head. A beautiful rock, about twenty pounds of it, and somehow I had to get over to it. The minute I saw it I knew that rock was just the thing I needed. This is going to take some doing, I thought, but I have to get my hands on that rock.

Gorgan yelled, “Get the lead out, Surratt! This ain't no goddamn picnic!”

Gorgan was one of the prison guards, a red-faced, hairy-armed anthropoid, sadist by instinct, moron by breeding. His lips curled in a grin and he lifted his Winchester 30-30 and pointed it straight at my chest. There was nothing in the world he would like better than an excuse to kill me. He had had his eye on me for a long time.

You sonofabitch, I thought, if you knew what was good for you, you would pull that trigger right now, because five minutes from now it's going to be too late!

But not now. Right now I was going to be the model prisoner, I was going to dig into that stinking, smoking asphalt and I was going to let Gorgan enjoy himself. In the meantime I had to get to that rock.

There were fourteen of us out there, twelve prisoners and two guards. We were right out in the middle of God's nowhere. Somebody had got the bright idea that the prison needed an air strip, a place where the State dignitaries could set their planes down. So that's what we were doing out there, building the air strip.

We were about three miles from the prison, four miles from the main highway, and about six miles from the prison town of Beaker. Hard against the prison, to the south, there was a big oil refinery, so we had to get on the other side of the refinery to build the air strip. The only reason we were left out there with just two guards was we were trustees. Pounding scorching asphalt ten hours a day, under a hundred degree sun, was supposed to be a privilege.

Well, I was going to kick their privilege right in the face!

But first I had to get to that rock. It was about twenty feet from us, over by the edge of the asphalt strip, so I began working my big wooden smoother over in that direction. Gorgan, feeling that he had got a hook in me, was reluctant to let it go. He moved over to the edge of the strip, that 30-30 still aimed at my heart.

“Get the lead out, Surratt! This ain't no goddamn picnic!”

One dump truck had emptied its load near the end of the strip and was now headed back toward Beaker. Another truck was just beginning to tilt its bed. This would be the last truck we'd see for at least an hour—which was fine, just the way I wanted it. But I had to work fast now. I had to get things started before that truck driver finished unloading.

I lifted my head for just an instant, just long enough to get the complete picture in my mind. The other prisoners were slightly ahead of me, with their heavy smoothers, tampers, rakes, wading ankle deep in that steaming black slush. The other guard, a kid of about twenty-three, was over by the water keg having himself a smoke. I heard the dump truck's winch growl, the bed tilted sharply and the black mass poured into a smoking pile on the ground.

The time had come.

I looked at that rock; I looked at it harder than I ever looked at anything in my life. I could almost feel that 30-30 of Gorgan's and knew that he still had it pointed at me. There was absolutely no telling what an idiot like Gorgan would do at a time like this. This was the most dangerous moment. The rest of it was planned—right at this moment, John Venci was waiting for me in Beaker. Five years I had worked on this, and it was perfect—all but this particular instant. I had to drop my smoother; I had to bend down and pick up that rock; and I had to do it while looking right into the muzzle of that Winchester.

I prayed that Gorgan's neolithic brain was working. If his brain worked, I was all right. If he simply reacted, like an animal, then I was sunk. That trigger finger would twitch and I would never know what hit me.

It was a calculated risk. I had to take it.

I kept staring at that rock. I had to slip the clutch before I started. I had to somehow make contact with that apelike mentality of Gorgan's, and the best way to do it was through curiosity. I stared at that rock as though it were the great-grandfather of all the rocks in the world. I grunted, as though in amazement. Then I dropped the smoother. I bent down and took the rocks in my hands.

“Surratt! Goddamn you, I told you once... 1”

I held the rock tenderly. I held it as though it were pure gold. I had gotten away with it! I had aroused the ape's curiosity!

“Mr. Gorgan,” I said, never taking my eyes off that rock, “this is the damnedest thing I ever saw!”

“You bastard!” he snarled, “put that thing down and pick up that smoother! Or maybe you want to know what a 30-30 slug in the guts feels like!”

I had him hooked. I could feel it. He was looking at that rock and not paying so much attention to his rifle.

“Look at this, Mr. Gorgan!” I said. “What do you make of this?”

He was hooked, all right! He forgot for a moment that he hated me. The ape thought he had found something. Something valuable, maybe, or anyway something very curious. He moved toward me, his flat, red face jutting forward.

His forehead wrinkled perplexedly, almost as though he were in pain. “What the hell! It's just a rock!”

“But look at this, Mr. Gorgan!” I pointed to a place on the rock—a place where there was nothing. Gorgan came closer. He saw nothing.

At that instant I think Gorgan knew he was as good as dead. I could see it in those animal-like little eyes.

That was when I brought the rock up with all the strength I had in my two arms. It cracked the point of Gorgan's chin and I heard his jawbone snap under the impact.

He didn't make a sound. He dropped his rifle and started to fall.

It was very fast and clean. I felt the strength of ten men as I watched him sprawl out with his face in the hot asphalt. “Good-by, Gorgan,” I thought. Then I picked up his rifle and shot him.

The other guard, the twenty-three-year-old kid, was still over by the water keg. He looked as though the sky had fallen. I started to yell and tell him to leave his rifle alone and he wouldn't get hurt, but I saw in an instant that it would only be a waste of breath.

He was a born hero, that kid. You could read it in every outraged line of his face. He made a dive for his rifle which was leaning against the water keg, but by that time I had made up my mind about heroes. He fired a quick one, a wild one, the slug missing me by a full fifty feet, and then I got the center of his chest in my sights and pulled the trigger. He jerked back, as though he had been hit in the gut with a hammer, and then he fell sprawling, a dead hero.

The truck driver was next. He was a smart boy and he certainly was no hero. I yelled for him to get out of the cab and he got out, fast, his hands in the air.

“Just stay there, just the way you are,” I said, and he nodded eagerly.

The other prisoners hadn't done a thing. They stood there like dumb cattle, too exhausted to make a move or a sound. The hell with them, I thought, and jogged over to the water keg and picked up the dead hero's rifle.

I called to the truck driver: “Start getting out of your clothes, and be quick about it!”

I skinned out of my dungaree prison jacket and trousers and got into the truck driver's blue work shirt and khaki pants. I felt like a new man.

“Do you have a watch?” I said.

He held out his arm, offering me his wrist watch.

“Mister,” he said tightly, “you want the wat

ch, take it.”

I laughed at him. “That's considerate of you, but all I want is the time.”

It was eleven-fifty, which was just about perfect. Noon is the dullest time of day—comes twelve o'clock and everybody knocks off for lunch, even cops. Even prison officials and truck drivers. That was how I knew that no more trucks would be coming to the air strip until the noon hour was over. If anybody wanted to spread the alarm, they would have to walk clear to the refinery, or to the highway which would give me plenty of time to make my contact with John Venci in Beaker.

“Don't get any cute ideas,” I said, “about slamming this truck into gear and getting away from me.”

His face was very pale. “Mister, do I look like a fool?” I laughed. “No, you don't. I'd say you're a very wise man.”

CHAPTER TWO

IT WENT LIKE clockwork. It couldn't have been more than twelve-fifteen when I parked the truck in an alley, behind a Beaker lumber yard.

I had been in the town before, but towns change over a period of five years, and it took a few minutes to get my bearings. To me the town was as exciting as Manhattan. Five years! I got out of the truck and stood there breathing in the air, smelling the smells. Who would ever believe that a man could gorge himself on thin, pure air!

I could do it. I drank it in like some fabulous gourmet tasting a really great wine for the first time, better than anything I had ever tasted before. It was freedom.

I was almost drunk with the realization that I was actually free. I walked away from the truck, and the dirty sidewalks of that dirty little town couldn't have felt better if they had been strewn with Persian carpets.

I noticed a clock in a jewelry store window, and that brought me back to the business at hand. I had almost finished with my part in the escape, and now it was up to John Venci. I didn't let myself consider the possibility that Venci wouldn't hold up his end of the bargain. He just had to be there, that's all there was to it. If he wasn't, then it was the end of Roy Surratt, and that was one thing I didn't let myself think about.

I quickened my pace and reached the end of Main Street where there was a service station—that was the first check point. Up ahead was a car. It was a new one and it was in the right place. I felt like laughing when I saw that car. It was all I could do to keep from running.

Then the roof fell in. I got even with the car and saw that it wasn't Venci at all, it was a woman. She just sat there, looking straight ahead. I felt as though somebody had opened my veins and drained out all my strength.

Where the hell was Venci! This was the place. I knew it was. But where the hell was he! I walked past the car and the woman didn't make a move. I could feel panic's cold hand on the back of my neck.

I walked to the end of the block and looked back. The car and the woman were still there, and there was still no sign of John Venci.

Get a good hold, Surratt, I told myself, because it's a long way down if you fall! I might as well face it; Venci wasn't there, and he wasn't going to come. Maybe something had gone wrong at his end, or maybe he had simply decided that the risk was too great and had forgotten it. From now on I was on my own, and the odds were a million to one that I would never get out of Beaker alive.

Venci I would take care of later, if I lived that long. Right now there was no time for anger. There was no time for anything except trying to think of a way to get out of this death trap before the alarm sounded. I thought of the freight yards, hitch hiking, stealing a car, and gave them all up immediately. Then I turned and headed back toward town, and I looked at that parked car again.

I knew what I was going to do.

I was going to take that car, woman and all. If the going got rough, she would be my hostage.

I walked around to the driver's side of the car, jerked the door open and said, “Lady, if you enjoy living, just don't make a sound.”

I ducked my head inside. She looked at me for just a moment, then said, “You must be Roy Surratt.”

I stared at her. “What?”

“I said you must be Roy Surratt. I'm Dorris.”

I just looked at her.

“Dorris Venci,” she said shortly. “John Venci is my husband. Now will you please get in the back seat; there are some clothes back there for you.”

She was no raving beauty, but there was something about her that got you. I said, “Mrs. Venci, you just about gave me heart failure. What happened to John?”

She frowned impatiently. “Later. Do you want to get in the back seat or don't you?”

I opened the door and got in the back seat. Laid out beside me was a complete set of street clothes. “Change as quickly as possible,” she said. “I'll let you know if anyone comes.”

I started peeling down without a second invitation. “While I'm doing this,” I said, “will you tell me what this is all about?”

“John is sick,” she said flatly, “so I came in his place.”

“What's wrong with him?”

She said nothing.

“All right, I was just asking,” I said. “Where do we go from here?”

“That depends on what we hear on the radio. If it seems safe we'll go all the way to the city where—where we have made plans for you. If anything comes up I'll have to drop you off with some people I know.”

I looked out the back window; the street was deserted. I said, “I'm a little out of practice with ties. Have you got a mirror?”

She got one out of her bag and held it up. What I saw was a sun-browned man of thirty-four, dark hair, regular features. He was no matinee idol, but he wasn't bad looking, either.

“Do you want me to drive?” I asked.

“Yes, that might be better.”

I got out of the back seat and into the front, under the wheel. She said, “Was there much trouble?”

“No trouble at all,” I said. “It went like clockwork. But we'd better get out of here pretty quick because in about thirty minutes hell's going to break loose.”

Dorris Venci said, “It doesn't seem possible that an escape could be brought off with no trouble at all.”

“Well, there were two guards. I had to kill them.”

She looked at me. “That's nice,” she said. “I'm glad there wasn't any trouble.”

“I tell you it's all right, Mrs. Venci. It will be at least thirty minutes before anybody finds out about it. There's nobody out there but a few prisoners and a truck driver. By the time the news gets out, we'll be a long way from Beaker. Everything was planned and everything went just the way I wanted it.”

She said, “Do you know how to find State Highway 61?”

“Sure.”

“All right, if you are through congratulating yourself, perhaps we can get started.”

I laughed. “Whatever you say, Mrs. Venci.”

We got out of town and on the highway with no trouble at all. I kept looking at myself in the rear view mirror; I couldn't get enough of looking at myself in a tie and clean white shirt. I had killed Gorgan; I had made my escape; and now I was behind the wheel of a sleek new automobile.

I didn't know the radio was on until it suddenly blared out: “GREENLEAF CALLING CAR 2021”

That is all there was to it.

“What was that?” I said.

“The radio is tuned to the State Highway Patrol frequency,” Dorris Venci said. “Car 202 is beyond our range; that's why we couldn't hear the reply.”

“But we can hear the Patrol headquarters. Is that right?”

“Yes. When news of your escape reaches the prison officials they will notify the Patrol.”

“And the Patrol will notify us.”

“If we are still within range.”

That short wave radio made a great impression on me. Why, with a thing like this working for him, a man could get away with murder! They'd never catch him. Then I thought: What are you thinking about, Surratt? You are getting away with murder, right this minute!

I looked at Dorris Venci, really looked at her, for the

first time. Until now I had been much too busy with myself to pay attention to anything else, but now that it looked like clear sailing I turned my attention to John Venci's wife.

My first impression of her had been pretty accurate. She was good looking, but certainly no raving beauty. She was a pretty good sized girl, maybe five-six, with a rather prominent bone structure. She had a good figure, too—maybe not one to stop traffic, but plenty good enough. All a man could reasonably ask for in a woman.

Her eyes were what stopped you. I decided. They were large and dark and very clear. Looking into her eyes was like looking into a pair of beautifully polished Zeiss lenses; they gave you a feeling of great depth and emptiness.

She could have been thirty five or twenty-five—sometimes it is hard to tell about big girls. The longer I looked at her the more beautiful she seemed to get, but I put that down to my being locked away from women for five years.

I hadn't even known that Venci had a wife, but there were a lot of things about Venci that I didn't know. Our acquaintance, although it had been very satisfactory, had been a brief one. An obscure gambling law had landed him in the State penitentiary for a short stretch, and for a few days we had been cell mates. We hadn't dwelt on personalities at all—only ideas; so it wasn't surprising that he had failed to mention Dorris.

“What time is it?” I asked.

She looked at her watch. “A quarter of one.”

“It won't be long now. I'd like to see that warden's face when he gets the news. What did I tell you? Nobody but a handful of convicts know I've escaped.”

The radio made a liar out of me. We were moving out of line-of-sight broadcast range, but not so far out that we couldn't hear Patrol headquarters when the news broke. Both of us listened intently for several minutes as my description was given: a description of the truck driver's clothes that I was supposed to be wearing, a description of the truck I was supposed to be driving.

I laughed. “What a shock they would get if they could see their escaped convict now, decked out in an oxford gray suit, driving a new Lincoln, a beautiful woman beside him.”

The Long Vendetta

The Long Vendetta The Law of the Trigger

The Law of the Trigger Whom Gods Destroy

Whom Gods Destroy Never Say No To A Killer

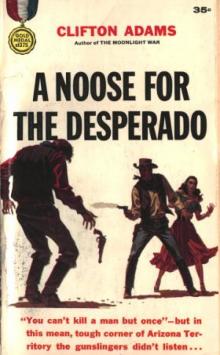

Never Say No To A Killer A Noose for the Desperado

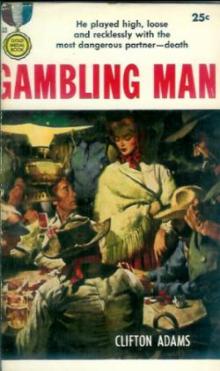

A Noose for the Desperado Gambling Man

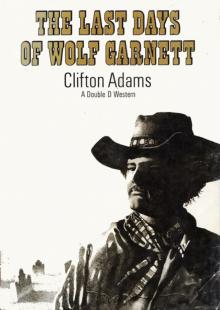

Gambling Man The Last Days of Wolf Garnett

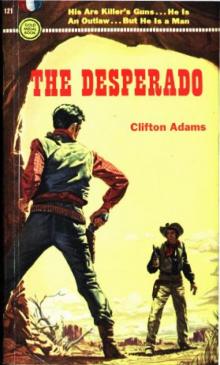

The Last Days of Wolf Garnett The Desperado

The Desperado Boomer

Boomer Death's Sweet Song

Death's Sweet Song The Colonel's Lady

The Colonel's Lady