- Home

- Clifton Adams

Boomer Page 13

Boomer Read online

Page 13

He could easily forget that she had worn her best dress especially for Kirk Lloyd, but he could not forget how she looked in it as she pressed herself against him and said not once, but twice, “Joe, I love you.” It was what he had wanted to hear, he guessed, more than anything else, and he could not believe that she had ever said it before to anyone else. He could even forget that she had once loved Turk Valois, and that she had permitted Lloyd to look at her the way he had and think what thoughts he pleased—all that vanished in the past.

For a moment, at least. And he held her hard in the rough circle of his arms and her mouth was willing. A thing like this, he told himself, could not be faked or repeated. It was a thing that happened once, only once, in a lifetime, if a man was lucky, and he would not let the past rear up and spoil it now.

For a long time neither of them spoke, and it was very quiet there in the gray gloom of the dugout. Grant was vaguely aware of the clean smell of the earth, and the sharpness of hardwood ashes and lime on the whitewashed walls, but the thing he would remember longest was the fragrance of Rhea's hair, the ghost of lavender.

Only after several minutes had passed did reality slip back into the room. And she asked quietly, her cheek pressed against his chest:

“Joe, will you stay?”

“Yes. If Lloyd goes.”

He felt her body go rigid against him. Suddenly, her eyes flashing, she shoved herself away, and when she spoke her voice hissed like water on a hot stove lid. “Get out! Get away from me!”

Her teeth bared almost wolfishly, and the flush of shame was in her face. “Get out!” she hissed again.

He drew himself up as tall as possible, unaware that this gesture toward self-righteousness might be a bit ridiculous. “All right, Rhea, I'll get out.” But then, as he reached again for the door latch, a strange thing happened. She made no sound but something discomforting happened to her face; a flatness appeared in her eyes, the snarl left her lips, and slowly her expression of rage began to break up and lose its definition. Suddenly she turned her back to him but made no sound. Only after several seconds had passed did he realize that she was crying.

This was the one thing that he had not been prepared for. At her father's funeral she had not cried, nor had she shed a single tear for Bud when the boy lay wounded in Doc Lewellen's sickroom, but now she sobbed, silently, her face turned toward the far wall of the dugout.

Instinctively, Grant started to move toward her, but the impulse was short-lived. He reminded himself bitterly that he had played the fool twice, falling for her tricks like a backwoods dolt, believing her lies. He did not intend to be tricked again. He lifted the latch.

“Good-by, Rhea.” He left the dugout quietly, as one would leave a sickroom.

I'm well, he told himself sternly, standing for a moment on the top step of the dugout. It's like I've been sick of some strange disease, and now I'm well. It's over.

But he did not feel well. He was not even sure that he was glad that it was over, but there was a limit to how much punishment a man's pride could take. Numbly, he buttoned the collar of his windbreaker. The wind slashed over the prairie basin like the backlash of a saber. The sky was a bitter gray, as hard as gun steel; here was a dry, treacherous cold that could freeze a man into immobility without his knowing it. A line day for the end of the world, he thought grimly.

But it was not a new experience. Once before, when he had quit the trail, one of his worlds had ended. And again when he had quit the farm and made himself an outlaw. But somehow this was different from the others; he was not leaving a way of life this time, but a dream, all wrapped up in Rhea Muller. He had known from the first that it was hopeless, but a thing like that doesn't stop a man from dreaming.

He grinned with bitter humor. Joe Grant, a man born less than a month ago on a Missouri creek bank, was no better off than the hard-scrabble farmer who had robbed Ortway in Joplin.

For a moment he let his gaze rest on the near-finished derrick and the reluctant builders working in the bitter cold. Well, with a killer on the pay roll, and with Valois' help, maybe Rhea would get what she wanted, if she knew what that was. And he tried to put her out of his mind as he tramped up the clay slope toward the bunkhouse. But it was not quite so simple as that. Even through his anger he could still see her standing there in the dugout, looking beautiful, yet ridiculous, in that new white organdy dress. A cold, beautiful, ambitious, scheming woman, crying silently, for what reason he could not, or dared not, guess.

As he stepped into the dry, acid heat of the bunkhouse, Kirk Lloyd said, “I was waitin' for you, Grant.”

Grant stopped short, faintly surprised to see that the gunman had made himself so completely at home on the Muller lease. Lloyd had stowed his scant gear neatly beneath his folding cot and was now sitting slouched near one of the oil-drum stoves. In his hand he held his .45, the muzzle pointed carelessly at Grant's chest.

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

“COME IN, MR. GRANT,” the gunman said dryly, motioning casually with the revolver.

Carefully, Grant closed the bunkhouse door and latched it. He glanced quickly at Bud Muller who had a cot next to the far stove, and the boy said, “What's the meaning of this, Grant? What's this gun shark doing on the Muller lease?”

“Your sister just put him on the pay roll,” Grant said, never taking his eyes from the gaunt, half-grinning Lloyd.

Bud made a short, explosive sound of anger, which was quickly cut off by an exclamation of pain as he lurched up on his cot. “I don't believe it! Rhea wouldn't hire him; why, just three days ago he tried to kill me!”

“She hired him just the same,” Grant said, and as he moved across the floor toward his cot, Lloyd's revolver followed him, staying fixed on some invisible point near the center of his chest.

“But I tell you Rhea wouldn't...” The boy started again, and this time the gunman showed his first sign of irritation.

“Shut up, kid, before I finish the job I started the other night! Grant's right: I'm workin for your sister.”

“It's my lease as much as Rhea's! I say you're not!”

Lloyd chose not to hear him, chose not to see anyone in the bunkhouse but Grant. At first he looked puzzled when Grant went straight to his own cot and began dragging out his gear —his saddle, a small blanket roll. Then the gunman gave a snort of surprise when he saw Grant remake the roll, lashing it doubled in a horseshoe for traveling.

“I guess you've got more sense than I'd figured on,” Lloyd said, and it was Grant's turn to pause and look surprised.

Grant frowned. “I guess I don't know what you mean by that.”

“Sure you do. I've just been hired to ramrod this operation. The first thing I aimed to do was run you out of the Territory, but it looks like I can save my breath.” He leaned back on the cot, gingerly favoring his left side, but the muzzle of his revolver held steady. “All right,” he said flatly, “get packed up and clear out. You're lucky I didn't decide to kill you.”

Grant tried to overlook the gunman's implication. “I'm clearing out, but not because you told me to, Lloyd!”

The gunman laughed; it was a curious sound, completely without humor. “You can believe that if you want to, but not me.” And his voice was suddenly harsh. “Now get your plunder together and don't let me see you again on this lease!”

Grant could see the bitter humor in the situation but that did not make it easier to swallow. He could not explain what had happened in the dugout after Lloyd had left—it would only make him look more ridiculous than he already did.

But it was not pleasant looking into Bud Muller's wide, bewildered eyes as he said, “Good-by, Bud.” The boy turned his face away in anger, and the gunman laughed.

Grant felt the anger piling up inside him and knew that he had to get out fast if he was to go out at all. He shouldered the saddle, took up his roll, and tried to make the door before Lloyd could say anything else.

“Just a minute.” The gunman stood up beside the stove.

“This is almost too easy. I kind of had the feeling there was something between you and the kid's sister, but I guess I was mistaken. She's the kind of girl a man fights for, if he has to.”

Grant shoved through the door and stood for one long moment against the bunkhouse, turning his face to the cutting wind, hoping that it would cool the anger inside him.

A part of his mind told him that he was smart, and he congratulated himself for that. What chance did he have against Lloyd with a drawn pistol? The gunman had been waiting for an excuse to kill him. Besides, what difference did it make if Lloyd thought he had been buffaloed?

And if Rhea got herself into trouble—well, she had asked for it when she put a killer on her pay roll.

Walking away was not easy, but walk he did. Past the shuttered, mud-daubed dugout, past the derrick. Two thousand dollars in his belt and he didn't even have a horse to ride. He paused briefly to shift his saddle to the other shoulder, then headed doggedly toward Sabo.

Sabo now was something of a city in its own right and had ceased to be a mere stopover between the discovery well and Kiefer. Less than a month ago there had been nothing here but a single frame building known as the Sabo Mercantile Company, a lonesome place in a lonely land, catering to the Indians and a few scattered ranchers; now there were close to a thousand tents, shanties, and buildings overlooking this strange new forest of man-made derricks sprawling out along the rim of the Glenn Basin.

It was shortly after noon when Joe Grant tramped cold and stiff into that maze of noise and confusion. He had no plan except to get away from the Nation, away from the Territory as fast as possible.

Unlike Kiefer, with its mile-long main street of shanties, Sabo lay sprawling and shapeless, milling with freighters and hacks and saddle horses. Here in canvas and sheet-iron flophouses the roustabouts gathered, the smell of Bartlesville and Bowling Green still in their grimy corduroys. And in the more pretentious clapboard “hotels” tool-dressers and drillers mingled with land speculators, gamblers, businessmen, and a few of the more adventurous eastern dandies, all acutely aware of the acrid smell of illusive wealth that swirled like some exciting fog over the basin. Here sharp eyed land men dealt for quarter sections near the discovery well which they would cut, with the precision of a skilled surgeon, Into a thousand small and worthless pieces and peddle them as vain able properties to gullible investors in Massachusetts or New York.

Here was a boom town, loud and crude as any trail town, unpredictable and dangerous as a tiger. Grant shifted his saddle and waited while a giant freighter with a twelve-mule hitch rattled past over the frozen ground. He felt the excitement here, and the greed, and the lust for sudden wealth was etched in every face and stared out from every eye. Even the cowhands from the Cherokee country and the old Outlet had been drawn away from routine herding jobs to sniff this new smell of oil and taste the excitement. And many of them had not returned.

Grant smiled thinly, continuing his plodding march toward a livery barn, dodging tents and shanties, wagons and impatient teams as he went. He told himself that he was glad to be leaving. Violence and greed were the urge of youth... and he was no longer very young. Maybe, after it was all over, he would look back on this day and consider it the luckiest day of his life—the day he had pulled away from Rhea Muller.

But he didn't feel lucky now, and he didn't dare look back. He kept his steps and thoughts going straight ahead.

Now, he had to stop again beside the flapping canvas of a tent restaurant while another freighter rattled past. And a voice behind him said:

“You aiming to leave our fair city, Grant?”

He wheeled as though a gun had been shoved in his back. Jim Dagget,' dry, humorless, perpetually angry, gazed flatly at him from under his wide-brimmed hat. Slowly Grant lowered his saddle and rested it on his hip. “Is there a law against leaving Sabo?”

“Maybe there ought to be,” the marshal said tonelessly, his pale eyes digging at Grant's face. “Why're you leaving?” Grant shrugged and unconsciously tugged his hat down on his forehead. “I'm not working on the Muller lease any more.”

“Why?”

The way he said it shot a chill of warning up Grant's back. “Would that be any of your business, Marshal? Officially?”

Surprisingly, Dagget shrugged and let the subject drop. “Maybe not. It's kind of a coincidence, though, running into you like this today. I was just on my way to the lease to pick up Turk Valois.”

The warning went up Grant's back again, colder this time than before.

Dagget smiled faintly and it seemed that his grim face would crack with the effort. “Surprises you, doesn't it? Well, it surprised me, too. You'd think Valois would be too smart to try passing stolen money this soon after a robbery.”

Those pale eyes kept darting at Grant's face and he couldn't meet them. Although the wind was bitter cold, his palms and forehead felt sweaty. “What,” he asked, “is that supposed to mean?”

“The money Valois gave Battle in payment for the Muller derrick timbers, remember? It made me curious. So I checked with a bank up in Joplin—one that was robbed not long ago— to see if they had the serial numbers of the stolen money.”

There was a numbing ache in Grant's chest and he realized that he had been holding his breath.

“What did the bank have to say?”

“They had the numbers, all right, and they matched the bills that Turk gave to Battle. Well...” And he stood there for a moment, unsmiling, his face showing nothing. “I guess that's all there is to it. Sooner or later we catch them, Grant. All of them.”

Grant stood frozen, and all he could think to say was: “I haven't seen you catch the man that killed Zack Muller.”

Dagget's face cracked again with that tortured smile. “I will. You can bet your life on it!” And he wheeled suddenly, a squat bulldog of a man hunched into his shapeless, fur-lined windbreaker. Then, almost as an afterthought, he turned again and said, “I hear Kirk Lloyd went to hire on with the Mullers. I hope Rhea had the good sense to turn him down; Kirk's got a reputation with women. And it's not a good one!”

Grant stood motionless for one long moment, watching Dagget's broad back bob and weave among the wagons and teams and finally disappear in the confusion of clapboard and canvas. Urgency was on the wind, an impulse to run grew up inside him, but he stood there motionless, trying to make sense out of what Dagget had said.

For the moment, he told himself, he was safe. But Dagget would not be fooled long. Ortway, the banker, would not identify Valois as the robber—and anyway, the runner would yell his innocence at the top of his lungs and then the whole story would come out.

Quickly Grant shouldered his saddle again and headed once more toward the livery barn. No, Dagget would not be fooled for long, but with a little luck it would be long enough for him to buy a strong saddle animal and get a good start out of the Territory.

The public corral had been built near the edge of town when Sabo was only a few days old, but the mushrooming boom town had since grown up around it. That steaming manure piles sided tent restaurants and flophouses passed unnoticed in this place where filth was taken for granted and griminess as a sign of wealth.

Grant slung his saddle to the ground beside a row of rental buggies and buckboards and quickly scanned the saddle animals inside the pole corral. The liveryman, a small man heavily weighted in a buffalo coat, came out of the barn and raked Grant with a pair of calculating eyes.

“Buy or rent?”

“Buy.” Grant indicated a tall gelding against the far fence. “How much for the black?”

The liveryman spat and brushed tobacco juice from the front of his coat. “Two hundred.” And when he saw the man hesitate he turned to re-enter the barn. At another place the animal would have brought seventy-five dollars, or maybe a hundred. But this was a boom town where double price was considered cheap.

Grant sighed and felt the money belt about his waist. He called to the liveryman and the deal was made.

It didn't do much good to tell himself that Rhea Muller was none of his concern—that she had deliberately asked for the trouble that went with hiring a gunman. Turk Valois was a queer one, but he had his pride and a kind of honor that Grant could understand. With that kind of man you could hate his guts and still not be afraid to leave him to look after your wife... or the woman you loved.

And Grant knew now that he had been counting on Valois to keep the gunman in line. Not that the runner could stand up to Lloyd with a gun, but there was something tough and ungiving about the man that made you know that he was strong in many ways where strength was needed.

It was strange, thinking of Valois this way. Grant hesitated before climbing to the saddle, wondering what Rhea would do if Dagget took the runner away.

And Dagget would take him away. Valois would yell, but that wouldn't stop the marshal from holding him until he could prove his innocence.

Goddamnit! Grant thought with sudden, unexpected savagery. What do I care whether or not he holds Valois? What do I care what happens to her?

But when he climbed atop the gelding he found that anger was not enough. It should have been an easy thing simply to bring the animal about and ride away from Sabo, but he did not find it so easy when he tried. Instead, he found himself wondering if there might be some way that he could clear Valois without putting his own neck in Dagget's noose.

The Long Vendetta

The Long Vendetta The Law of the Trigger

The Law of the Trigger Whom Gods Destroy

Whom Gods Destroy Never Say No To A Killer

Never Say No To A Killer A Noose for the Desperado

A Noose for the Desperado Gambling Man

Gambling Man The Last Days of Wolf Garnett

The Last Days of Wolf Garnett The Desperado

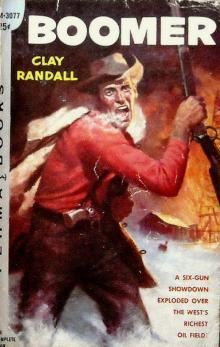

The Desperado Boomer

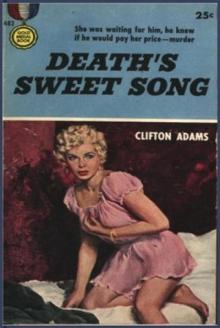

Boomer Death's Sweet Song

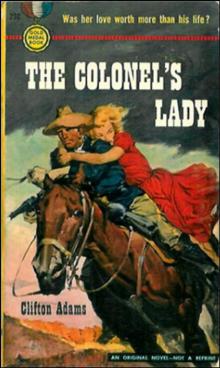

Death's Sweet Song The Colonel's Lady

The Colonel's Lady