- Home

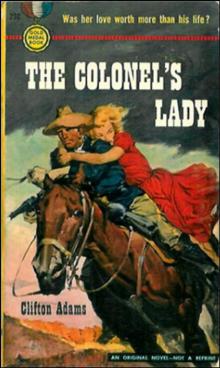

- Clifton Adams

The Colonel's Lady Page 2

The Colonel's Lady Read online

Page 2

I said, “You didn't know them, did you? The dead man and his wife and his kid?”

He looked at me without actually seeing me. “I know them. Not their names, but I've seen a thousand just like them, and I know them, all right. They're goddamn fools. They keep movin' west, right into the Indian country, and we can't hold them back. The Army threatens them and Apache kills them and still they keep comin'. Goda-mighty, what do they expect to find out here in this God-forgotten desert? Why don't they stay home?”

“Maybe they haven't got a home,” I said. “Maybe that's the reason they keep coming.”

Skiborsky snorted, but with no great conviction. It was a thing that he had given a lot of thought to, and it didn't add up to anything that made sense. They kept coming, the settlers, the homesteaders, looking for something, and Sergeant Skiborsky couldn't understand what. Maybe he had been in the Army for so long that he couldn't understand anything if it wasn't in the book of Army regulations.

“Get back to the grave detail,” he said abruptly, as though he were tired struggling with the idea. “We'll be movin' out of here before long.”

We did a good job on the graves, considering the tools we had to work with and the ground we had to dig in. We lowered the three bodies in, wrapped in the three Army blankets that the Fort Larrymoor supply officer would complain about later, and covered them up. We didn't know their names, so there was no use worrying about headboards. After it was all over and done Dodson walked off a piece and vomited behind a boulder. He didn't get hit in the face with a carbine stock, though, the way Skiborsky had threatened.

The whole thing had taken no more than half an hour, but the lieutenant was back telling us to hurry up before we were half through. The Apache war party that had killed the settlers, he said, must have been a small one—no more than four or five, according to the fresh trace left by their ponies. But he was afraid they had seen us and had gone for help. I didn't like to think of what would happen if they came back and ambushed us in one of those valleys with thirty or forty braves. The lieutenant didn't like to think about it either. We finished the job and the column began to roll again.

“You and Skiborsky seemed to be hittin' it off out there,” Morgan said, as we tried to get comfortable again in the wagon bed.

“He's all right. He's probably a good soldier.”

Morgan spat over his shoulder. “Maybe. I've got a feelin', though, that he'll get a chance to prove it to me before long. He can't prove it by knockin' around a kid of a boy.”

I looked at him. “I didn't know Dodson was a friend of yours.”

“He's not.” Morgan's eyes looked restless. The color in them seemed to deepen and glow with a dull, undirected hate. “It's just,” he said softly, “seein' a bluebelly sergeant knock a boy around. I never liked to see a bluebelly knock anybody around.”

I almost grinned at that. I said, “You're forgetting something. You're going to be a bluebelly yourself, as soon as they get us to Larrymoor and swear us in.”

He didn't have anything to say to that.

“I can't get over it,” Mayhew said thickly, and I hadn't realized until then that he was drunk. “Just think—some damn Apache goin' around with that woman's hair in his belt. And that man... Lord!”

“Shut up!” Dodson said abruptly, almost sobbing.

Mayhew's eyes looked stunned. “Now what's got into the boy? All I said was...”

“Dodson's right,” the small McCully put in sharply. “Shut up. We don't want to talk about it. And besides, goddamn you, you're drunk.”

Mayhew grinned slyly. “Drunk? Why, sir...” But his eyes lost their focus and his brain lost the thread of the thought and his chin sank to his chest. He slept, falling against the stern-faced McCully, saliva bubbling thickly at the corners of his mouth.

“Goddamn,” Steuber, the Dutchman, muttered to himself. “What good are things to a dead man? Hell, I wouldn't of minded, if it had of been me.” He looked as if he had been done a great injustice.

The wagon jolted, grated, ground its way over the rocks of the desert. Our rumps were as sore as boils and even the saddle-hard Morgan kept scrounging around from side to side, trying to find a comfortable way to sit. Only the big Steuber didn't seem to mind. The Dutchman sat slab-faced, as solid as a rock, muttering to himself, sleeping when he felt like it, or gazing out at the monotonous land as if he still didn't believe that there really could be such a place. After a while I began to think again of Caroline.

I wondered how a man could hate a woman and still love her. I could wonder about it, but I knew better than to expect an answer.

Weyland... the name went around in my mind. That was her name now. Mrs. Major General Jameson Joseph Weyland, or was it simply Mrs. Jameson J. Weyland? What difference did it make? She wasn't Mrs. Matthew Reardon.

Weyland wasn't actually a general, of course. That was only his brevet rank, a rank he had held during the war, and now he was just another colonel with another God-forgotten, civilization-forgotten outpost to command. I had learned that much from listening to the troopers talk. Only a colonel, probably eating his heart out because he couldn't forget that he had once been a major general, but he had Caroline, goddamn him. I didn't know how he got her, but he had her, and I should have been thankful that I was through with her. But all I could do was to sit there and think darkly: Goddamn him.

A big hard hand was on my shoulder, shaking me. “For God's sake, Reardon, wake up.”

I had fallen asleep somehow, and the cool-eyed Morgan was shaking me. I braced myself against the side of the wagon and sat up.

“You've sure got a gutful of hate for somebody,” Morgan said, grinning thinly.

I looked at him, still groggy. “What are you talking about?”

“You was givin' somebody hell. Whoever it was, you was layin' it on with a whip.”

Morgan actually laughed. I glanced around and all the other men were looking at me, soberly, calculatingly. All but Steuber.

“There it is,” the big Dutchman said, leaning out of the wagon and pointing straight ahead. We all looked in the direction he was pointing and about a mile up ahead we could see it too. Fort Larrymoor.

Chapter Two

IN THE BOOKS at Washington they had Larrymoor down as being manned by a regiment of cavalry, whose job it was, with the help of other forts strung raggedly along the frontier, to keep the Indians fed, satisfied, and on their reservations. Maybe on paper it was a sensible plan. Here on the desert and in the hills it was something else again.

What they had at Larrymoor was called a regiment— because they had to give a colonel some kind of job to do, probably—but what it looked like was maybe two understrength battalions. How Weyland's superiors in Washington explained that other battalion of men that he didn't have, I didn't know. How Weyland himself explained his lack of troopers to the Apaches I didn't know either.

The fort was built of yellow adobe bricks mostly, because there was little timber to cut for logs in that country. We got a good look at it as the column clattered out of a rocky draw and clawed its way up a steep hillside toward the main gate.

Everything at Larrymoor was inside the four adobe and pulpwood walls. All the buildings were jammed together, as they always are in a fighting fort, the magazine next to the stables, the stables next to the one-story barracks, the barracks jammed uncomfortably close to a row of squat little adobe huts that would be Officers' Row. The headquarters buildings were against the back wall and away from the front gate and the stables, and in the middle was a big parade of packed clay. The whole thing was set on high ground, somehow proud in spite of its drabness, with sun-baked wasteland all around it. The only things we could see outside those walls were the sutler's store and the post cemetery. It was a large cemetery for a post that size.

The guards had the gates open for us and the column rattled inside and dragged wearily to a halt.

“By God,” the gambler, McCully, said, “this is a thousand miles from nowher

e.”

Skiborsky turned in the driver's seat. “You won't get lonesome, bucko. There's plenty Coyoteros less than an hour's ride into the hills.” He grinned. “Maybe some Chiricahuas and Pinalehos too, if Kohi really means business. And I reckon he does.”

I knew that not even Cochise, chief of the Chiricahuas, had been able to bring the Apache tribes together and hold them together. I doubted that Kohi, the White Mountain war chief, could do it for the Coyoteros.

I found myself staring, searching for something; and then I realized that I was looking for her. I wanted furiously just to look at her. But she wasn't there. She would be in one of those huts on Officers' Row, being Colonel Jameson Joseph Weyland's wife, and I would bet a month's pay that she wouldn't be liking it. Somehow the idea that she was miserable made me feel better.

We got out of the wagon, stiff-legged and awkward, while Skiborsky lined us up and looked at us contemptuously. He took off his shabby forage cap, blew some dust off it, and set it squarely on his head. He beat some dust from his sweat-streaked blouse and some more from his trousers, then he jerked erect as stiff as a board and became an entirely different man, a soldier.

He about-faced as though he had been jerked half around by a pair of huge hands. “Forward! Ho-o-o!” Skiborsky marched at rigid attention all the way across the parade, to headquarters, the rest of us straggling along behind. Morgan was smiling faintly in amusement. “A goddamn tin soljer!” I heard him mutter under his breath.

Skiborsky's head snapped around to eyes-right. “Lock that jaw, trooper.”

“I'm no goddamn trooper,” Morgan said. “Not yet.” Skiborsky's mouth was a thin grim line, but I could see that fierce grin of his looking out from behind his eyes. “You will be,” he snapped. “You will be!” And I thought I heard him add, “Even if I have to kill you.”

We marched straight up to the headquarters porch, where a captain was waiting. He smiled faintly as Skiborsky went through the motions of bringing us to attention again, saluting, turning the recruits over to the officer.

“I suppose all of you want to enlist,” the captain said mildly, after Skiborsky had marched off toward the barracks. “We might as well get started.”

We went inside, where four enlisted troopers sat at desks, looking at us vaguely, without curiosity, without interest of any kind. They all began to reach for official-looking enlistment forms.

“Answer all questions,” the captain said. “After that's done there will be a medical examination and then I'll swear you in.” The captain got behind a desk and found a form and motioned to me. “I'll take you over here. We have to get this done before retreat or you won't be able to draw arms and supplies. Name?”

“Matthew Reardon.”

He wrote it down. “Age?”

“Thirty-two.”

He looked up to get the color of my hair and eyes and approximate height and wrote down what he saw. “Previous military experience?”

Without thinking, I said, “Four years.”

“Rank last held?”

I paused for a moment, and then decided that it didn't make any difference one way or another.

“Captain.”

His eyebrows came up at that, but he wrote it down. “Organization?”

“Thirty-sixth Alabama Horse.”

He put his pencil down and sat back and studied me. He said quietly, “We already have several men out of the Confederate Army. They're good fighters mostly, the same as the rest of our soldiers. Some of them, though, can't seem to remember which war they're fighting, or who is the enemy.” Then his eyes moved up and looked at mine. “When a man comes to Larrymoor, it's usually because he is afraid to go anywhere else. What are you afraid of, Reardon?”

We locked gazes for a moment. I had a feeling that he wasn't so interested in what I said, he just wanted to watch my eyes while I said it.

“The usual things that men are afraid of,” I said finally. “Death and insecurity and, of course, the fear of being afraid.”

He smiled. “I was afraid you were going to say 'nothing.' If you had, I would have sent you back to Tucson with the next supply train.” He fumbled in his breast pocket and came out with a ragged, dry cigar, and rolled it around between his fingers. All cigars, I thought, would be ragged and dry in this country. “Why do you want to enlist at Larrymoor?” he asked.

“The cavalry is what I know.”

He sighed, indicating that he hadn't expected much of an answer to that one.

“Have you any idea of what it's going to be like here?”

“Yes.”

“How long did you say you'd served with the Thirty-sixth Alabama?”

“Four years.”

“Then you ought to know enough to answer like a soldier.”

“Four years, sir.”

“That's better.” He smiled again, quietly, the way he talked. In the back of my mind I had been dreading the minute when I would have to say “sir” to a Yankee officer. It wasn't as bad as I'd expected it to be.

“The Thirty-sixth Alabama,” he said thoughtfully. “Weren't you at Cold Harbor?”

“Yes, sir, we were there.”

“And the battles of Johnson's Pond, and Three Fork Road?”

I felt myself stiffen. “Yes, sir.”

He kept looking at me, but his thoughts seemed to turn inward. “Perhaps,” he said, “you have already had the honor of meeting our commanding officer—on the field, that is. He was at Three Fork, you know. Led the regiment of Harrison's Brigade in the famous charge there. Famous, anyway, around here.” He colored slightly, as if he had said something that he shouldn't have.

It didn't hit me at first. I was just thinking that it was a rather bitter coincidence having Three Fork Road mentioned, and then, slowly, the real meaning caught up with me. Weyland had led the charge of Three Fork. The man Caroline had married!

“What's the matter, Reardon?”

I pried my mind loose from the past, but it was an effort and it left me weak.

“Nothing, sir.”

“You looked strange for a moment there. I meant no slight to the Thirty-sixth Alabama because of Three Fork.”

“It wasn't that, sir. It wasn't anything.”

I forced a small grin. For just a moment I could feel myself walking the razor-thin edge of hysteria, and there was an almost uncontrollable urge to throw my head back and laugh, for I was beginning to understand just how big a fool I had been. But I choked the feeling down and after a moment it went away, and the captain was saying:

“What I was going to say,” looking back at the enlistment form, “was that it won't be easy here for you. Have you ever served as a private soldier?”

“No, sir.”

“That won't make it any easier. We have men here who did time in your Confederate prison at Andersonville. Some of them will never forget it, I'm afraid.”

“Was Andersonville worse than the Yankee stockade at Fort Delaware, sir?”

He smiled faintly, without humor. “I know.” He started to say something else, but then a major came in and the captain stood up.

“Are these the new recruits, Captain Halan?”

“Yes, sir, there are six of them.”

The major, a squat rock of a man, with a fierce sand colored dragoon's mustache hiding a thin line of a mouth, nodded impatiently. “I can see there are six of them. How are they to be split up?”

“First Battalion has first priority on new men, sir. With the major's permission, I would like three of them. A Company is twelve men under strength.”

The major quickly referred to the morning report in his mind and nodded again. “All right. Three to A Company, one to C, and two to B. Have them sworn in and assign them to their units, where they can draw arms and supplies.”

“Yes, sir.”

The major glanced at all of us, not particularly happy with what he saw. His gaze lingered for a moment on Morgan. He took a deep breath, almost a sigh, and walked out. Three first sergeants

had appeared in the doorway in time to hear part of the major's speech. One of them, a big, rawboned Abraham Lincoln of a man, grinned widely while the other two glared about the room with bitter eyes. The grinning one, I guessed, belonged to A Company. He looked at Captain Halan and said:

“Ready, sir?”

“Pretty soon, Sergeant. Is the doctor on his way?”

“Comin' across the parade now, sir.”

The physical examination didn't take long. The contract doctor told us to take our shirts off and he thumped us and listened to our chests and noted scars and told us to put our shirts back on. He stood for a moment, studying Mayhew, then abruptly he closed a shutter over the doubt in his mind and said, “They'll do, Captain.” He walked out.

“All right,” Captain Halan said, “line up here and raise your right hands.” He took up a book of Army regulations and began: “Do you solemnly swear...”

A few questions, a few responses, and we were members of the United States Cavalry. Morgan smiled that cynical half-smile of his through it all. Steuber was passively sober. The others seemed slightly dazed.

Captain Halan closed the book. “Reardon, Morgan, Steuber, go with Sergeant Roff. As of now you are members of the United States Cavalry, the Regiment, attached to Company A of that regiment. Dodson and Mayhew, go with the B Company first sergeant. McCully with C.”

We walked across the parade as a twelve-man patrol rode through the gates, dust-covered, sagging wearily in their saddles, and headed for the stables. One of the companies was beginning to fall out as the bugler sounded first call for retreat. They looked hard and tough, almost picture soldiers in their dress uniforms and plumed helmets.

The Long Vendetta

The Long Vendetta The Law of the Trigger

The Law of the Trigger Whom Gods Destroy

Whom Gods Destroy Never Say No To A Killer

Never Say No To A Killer A Noose for the Desperado

A Noose for the Desperado Gambling Man

Gambling Man The Last Days of Wolf Garnett

The Last Days of Wolf Garnett The Desperado

The Desperado Boomer

Boomer Death's Sweet Song

Death's Sweet Song The Colonel's Lady

The Colonel's Lady