- Home

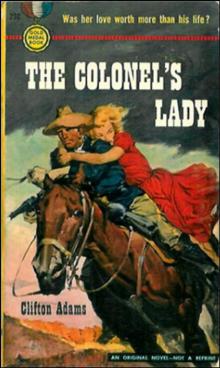

- Clifton Adams

The Colonel's Lady Page 5

The Colonel's Lady Read online

Page 5

I should have hated him, because I had planned to hate him. Somehow I felt sorry for him. I felt anger, but it wasn't for Jameson Joseph Weyland. Then the back door opened and Caroline stood in the doorway, smiling.

“Trooper Reardon?” She said it calmly, without turning a hair. Weyland was still within hearing distance.

I heard myself saying, “Yes, ma'am.”

“Come in, trooper, and I'll explain...” She let the words hang. The Colonel had disappeared into the headquarters building and there was no reason now for pretending.

I had made no plans. I didn't know what I was going to say or do. For a while it was enough just to stand there and look at her. Time, it seemed, had no effect on Caroline. She looked the same to me as she had five years ago; still beautiful with a pale, almost fragile beauty. Her hair was blonde and her eyes were as blue and as deep as the Arizona sky. Too blue and too deep, like the sky, to look into long at a time.

Still smiling, she said, “Come in, Matt.”

It was a fool thing to do, with the headquarters building less than fifty yards away. But I found myself going up the steps.

“You've changed quite a lot, Matt,” she said lightly, conversationally, in the tone of voice you would use in meeting an old vaguely remembered acquaintance, but not a friend.

I set the carpenter's kit down. “You haven't.”

She laughed lightly, musically. “That's nice of you,” deliberately ignoring the real meaning. “After all, it's been five years, hasn't it, Matt?”

“Five years, four months, and a few days.”

“My,” she smiled, “I hadn't imagined you would remember that well.”

“It isn't often that a cavalry officer loses his entire command, killed or captured. I remember the date without any trouble.”

Her smile flickered, almost went out. I could smell the cleanness of her, the lavender sachet and the briskness of crinoline and laces. It was an exotic, heady scent when you're used to the stench of the stables and the man smell of the barracks. “Come into the front room, Matt,” she said abruptly. “We can talk better in there.”

“What would the Colonel say, Mrs. Weyland?”

“Does the Colonel need to know, Matt?” She turned, layers of petticoats rustling, and walked through a doorway toward the front of the house. I followed her, as she knew I would.

The house must have had five rooms; a mansion in a place like Larrymoor. The first thing that struck me about the front room was that there were curtains at the windows, starched, stiff white lace curtains rustling softly in a hot desert breeze. I had almost forgotten that there were such things. There was a big leather post-made chair, stuffed with horsehair and covered with horsehide; a massive tea table supporting a heavy silver tea service, two porcelain coal-oil lamps with hand-painted figures on the bases, a braided rug on the floor, wallpaper and pictures on the wall. Furnishings and luxuries that, on Caroline's orders, had been freighted half a thousand miles across the desert, simply because she was used to such things and had to have them around her. For me it was like walking into another world.

Caroline stood in the center of the room patiently waiting for me to say what I had to say. I walked slowly around the room, touching things, feeling of them and bringing back part of an almost forgotten past. On one wall there was a copy of Titian's moody St. Margaret in live greens and sober browns, contrasted on the other wall with the sharp, sure colors of El Greco. Those would belong to Caroline. I didn't think the Colonel would care much for painting, or for any kind of art, for that matter, except perhaps the art of war.

On a table by the leather chair, beside a cut-glass decanter of amber wine, were Weyland's books. I picked one out just for the sensation of touching it. Wallhausen's “Art militaire a cheval.” I glanced at the others. Machiavelli's “The Arte of Warre.” Romer's “Cavalry.” Nolan's “Cavalry Tactics.” Wood's “Cavalry in the Waterloo Campaign.” They were all there.

“Well, Matt,” Caroline said.

I put the book down and turned. “It's been a long time since I've had a book in my hand or seen a painting, even a copy. But an old Alabama gentleman doesn't wander about touching things, does he? I guess you were right. I've changed.”

“What do you want, Matt?” she asked coolly.

“I'm not sure.”

“Why did you come here?”

“You sent for me, didn't you, to do some carpentering, on your back doorstep?” I felt more at ease now. At least I could look at her without having to look immediately away. “By the way, how did you manage it? I'm not down on the records as a carpenter.”

Her sudden laughter didn't sound like laughter at all. “I simply told the Colonel that I wanted a carpenter by the name of Reardon. I told him that you had done some work for Major Burkhoff's wife.”

“But I haven't.”

Her face sobered. “What difference does it make?” she said impatiently. “I had to talk to you. It doesn't make any difference how I managed it.”

The thing that had been going around in my mind ever since Captain Halan had mentioned Three Fork Road began to take shape. Caroline could see it taking shape and she didn't like it.

“Answer me, Matt. Why did you come to Larrymoor?”

“Is that sherry?” I asked, nodding at the decanter on the table. “It's oloroso.”

It had to be oloroso. Nothing but the best for Caroline. I poured a wineglass half full and drank it, throwing it down without tasting it, the way Skiborsky would throw down the sutler's whisky. I poured the glass full and replaced the glass stopper and sat down in the Colonel's chair. Not because I wanted the sherry or because I was so tired that I couldn't stand up. I wanted to see what Caroline would do.

She didn't do anything, didn't even blink.

“I've heard,” I said, “that Weyland was at the battle of Three Fork; led the Union cavalry charge there, in fact. But you wouldn't know anything about that, would you, Caroline?”

She still didn't move, but I saw a certain uneasiness in those eyes of hers.

“It's the truth,” I said, “about not knowing why I came to Larrymoor. Maybe just to see you again. To look at you and wonder what kind of woman you really are. I'm not even sure why I came to Arizona, except that there wasn't much left for me in Alabama after the war. The plantation's gone. When I got back, the darkies were too drunk with their new freedom to work for any wage, so the cotton went to pot. What cotton we had baled went to the treasury agents. And there were a lot of debts. Well...”

I looked at her over the wineglass.

“You remember our place, don't you, Caroline? And the time you came down from Virginia, to visit your cousins the Blackwelders, and the parties we had in those days? The South isn't the same, Caroline, but I don't suppose you would know about that. There's not much there. Old families are broken up, and the great plantations are broken up too, or in weeds. You knew it was going to be that way, didn't you? After the Wilderness campaign there wasn't much doubt about who was going to win the war. And you didn't want to be on the losing side, did you, Caroline?”

She reacted to that. She took three quick steps toward me and slashed my face with the flat of her hand. “Get out!” she rasped like a den of stirred-up rattlers. “Get out before I scream!”

But I wasn't ready to leave now. I had too many things inside me that had to come out, and I had to be sure of things. I had waited a long time and had come a long way, and now I had to know.

“Are you going to get out?”

“No. Not yet.”

“I'll scream.” Her voice was cold with anger. “Do you know what they will do to you? I'll tell them—I'll tell them you attacked me!”

I had to smile at that. She wouldn't scream and I knew she wouldn't, because she had to know why I had come to Larrymoor. She took a deep, shuddering breath and got hold of herself. She sat stiffly in a graceful little dark mahogany chair and glared at me.

Maybe she was afraid of me. Maybe she was hating me. But she

pulled the shutters behind her eyes and I couldn't tell. I knew now that I had never been able to tell what Caroline was thinking, not even in the old days when I thought I knew everything, and the thought was disturbing.

So I talked.

“Do you remember, Caroline...?”

She remembered, all right.

Before the war we had had a plantation that we called Sweetbriar. It was my family's plantation. Not the greatest in Alabama, but not the smallest, either, especially along the Black Warrior River, where we lived. The land was black and rich and earthy smelling, not like it was here on the desert, where the land is baked to lifelessness under the blast of an everlasting sun. We had seventy-four slaves one year—although that was an exceptional year and so long ago that I hardly remember—and in the fall of the year the darkies would begin preparing for the great barbecues we used to have, and the parties. That was the time for parties, the fall and winter. It was at one of those wonderful parties that I saw Caroline for the first time.

I thought back for a moment, recalling whole pigs roasted with unbearable slowness for days, turned on spits above hickory coals in pits and basted with honey and fine old amontillado until they were crackling brown. And the guests that would come, arriving in their glittering Victorian carriages and staying for days, eating, drinking eight-year-old bourbon saved for the occasion, and dancing in the evenings to the music of Captain Fitzhugh Dunham's brass and string orchestra, brought all the way from Birmingham. They knew how to have parties in those days.

I remembered one in particular—not at Sweetbriar this time, but one that the Blackwelders gave in Caroline's honor. I could look back and imagine the way it was, the way it must have been, but somehow it didn't seem real now. Still, I could recall old Rowel Blackwelder looking vaguely ridiculous in his skin-tight pants and velvet jacket, bowing low—and painfully, for he was in his seventies—and saying, “Matthew, I have the honor to present our lovely niece from the great state of Virginia.”

I must have fallen in love with Caroline that very night, as Captain Fitzhugh Dunham's brass and string orchestra played “Annie Laurie” in three-quarter time, and we danced.

What year was that? I wondered now, with Caroline still studying me from behind the shutters of her eyes. The year of grace 1859, that had been the year, and both of us were very young. I had never even heard of a place called Fort Sumter then.

But before long we began hearing the warning rumblings around us and Caroline's father wrote for her to come home. And then a soldier's hand pulled a lanyard in Charleston....

“Don't forget me, Matt,” Caroline said. And she meant it, too, I think, at the time. I made the trip from Sweetbriar to Birmingham, with the Blackwelders, to see Caroline on the train that would take her back to Virginia. How could I forget her, I thought, when I was already so in love with her? But I couldn't say it there, with her cousins and uncles looking on.

“There won't be time, Caroline,” I said. “Likely we'll all be in Virginia before long, to finish up this war. I'll be sure to see you there.”

We were already organizing a company of cavalry, the young men from the plantations along the Black Warrior River. We got together four times a week and rode up and down Oak Grove Road in what we took to be military formation, and on Sunday afternoons we practiced with our hunting muskets until we ran out of powder and ball. There was a great excitement in those days, for the South had already won a spectacular battle at Bull Run, and we all had uniforms made of the finest gray flannel and we began to think of ourselves as soldiers.

There was a great to-do about us at all the parties. The girls presented us with enormous black ostrich plumes to adorn our wide-brimmed hats, and they tied brilliant silken sashes around our waists, and we all cut gallant figures as we rode from one party to another. Then at last, with a great many tears and kisses and promises, we rode bravely off to Birmingham to become part of the Thirty-sixth Alabama Horse.

Now, as I thought back on it, it was almost amusing to remember the way we rode into the war. It was a lark, like being on our way to an extra-big barbecue, the biggest barbecue the South had ever seen, and the most exciting. We brought our Negro houseboys with us to keep our uniforms neatly cleaned and pressed and to do our cooking and to serve us. We brought wagons full of clothing and bedding and a great quantity of delicacies such as smoked hams and chicken and dozens of jars of strawberry and watermelon preserves. We had also two full kegs of Monongahela whisky and one keg of Kentucky rye, to sip on, I suppose, while we whipped the Yankees in a strange sort of bloodless war where there was no discomfort of any kind, only glory. But we learned soon that war was not the way we had imagined it.

I visited Caroline at her own house in Virginia that spring. It was a great white house, larger even than Sweetbriar, and there was a large gay party of officers and their ladies when I got there. I was uncomfortable at first, partly because I was the only lieutenant present, and partly because I had never imagined a house grander and richer than our place at Sweetbriar. But Caroline's house was all of that.

“Matt,” she said, smiling, “I'm so glad you finally got to Virginia!”

I held myself stiffly erect, in what I took to be the correct posture of a soldier. “I got here as soon as I could. I'm with the Thirty-sixth Alabama, you know.”

“I know, Matt. You look very handsome in your uniform!” Then she lowered her voice and looked directly at me with those clear blue eyes of hers. “I've missed you, Matt.”

“I've missed you, too,” I said. “I've missed you so much... Well...”

“I know, Matt.” Then she smiled. “Let me introduce you to the other guests.”

I kissed her that night for the first time. She was supposed to be dancing with a major from some Virginia regiment or other—the Richmond Cannons, I think, but she came outside with me, out on the wide, pillared porch where the night was heavy with honeysuckle. Then, for no reason at all, seemingly, she began to cry.

“Caroline...” I shrank inside for fear that I had offended her. I was young then, and inexperienced, and I didn't know what to do.

“Matt, I'm sorry,” she said. “It's not because of you, it's just that everything is so perfect now, so gay and exciting, and the men are all so proud. It will never be this way again.”

I didn't know what she was talking about. I didn't realize then that she was wiser than most people in the Confederacy in those days, and already she was beginning to see the end of things. Or at least glimpse it, in some dark part of her woman's mind. '

“Matt,” she said, “hold me close. I'm afraid.”

We stood there for a long while, in the shadows, listening to the orchestra playing “Maryland! My Maryland!”—Virginia should not call in vain, Maryland!— to the tune of “O Tannenbaum,” and I felt very close to Caroline that night.

“Matt,” she said.

“Yes, Caroline.”

“You should be very glad that Sweetbriar is in Alabama and not in Virginia.”

It was a strange thing to say, I thought.

“Because the war is going to be fought in Virginia,” she said. “The Shenandoah will be wreckage and ashes before it's finished. Everything in the valley will be lost, including this very house where there is so much gaiety tonight. This very same beautiful house, Matt, along with everything else in Virginia, will be lost forever.”

“Caroline, don't talk like that!” I said in dismay. “The Southern forces are victorious on every hand. How could the North invade the Shenandoah?”

“I don't know, Matt. But I know they will.” Caroline was wiser than most, but not even she could imagine the ruin that was to come in the next three years of war.

I said, forcing myself to laugh, “There's always Sweetbriar, Caroline. Surely you aren't expecting the Yankees to raid into Alabama?”

That possibility was remote, even to Caroline. Then, with some new-found courage, I heard myself saying, “Sweetbriar could be your house, Caroline.”

She was silent for a long while.

“Do you mean that, Matt?”

“I love you. I'm asking you to marry me.”

It was not the way things were normally done, no formalities, no announcements. But those were not normal times. So that was the way it happened, as we stood there in the night, and the orchestra played that sad new song for the thousands of men yet to die:

“The years creep slowly by, Lorena,

The snow is on the grass again...”

And now, looking again at Caroline, I saw that she remembered.

“Hold me close, Matt. You're everything to me now. You're all I have,” she had said.

I didn't understand the meaning behind the words that night, but I could understand the softness of her mouth as I kissed her, the warmness of her young body as I held her against me.

“Matt, I'm afraid,” she said. “I wouldn't know what to do without you.”

We said a lot of things. I don't remember what, but they must have been similar to things lovers always say. Suddenly Caroline began shivering in my arms.

“The spring nights have a chill,” I said awkwardly. “Do you want to go back inside, Caroline?”

“Not to the ballroom. I don't feel like dancing.” I could hear fear in her voice and it disturbed me, for Caroline was not one to show such emotions. “Matt, don't ever leave me!”

“I won't, Caroline. Never.”

But she began to shake again and I started to take off my jacket to put around her bare shoulders. But she shrugged it off, impatiently, it seemed, and said she would go to her room and get a wrap.

“Shall I wait for you here?” I asked.

“Come with me, Matt.”

I knew what she meant, I suppose, but a great many generations of gentlemanly breeding attempted to cloak the words and give them new meaning. But there was a sudden hammering in my chest, and an excitement that I had never known before. I took her hand. “All right,” I said.

That night comes back to me now, still unreal in many ways. I can still hear the muted confusion in the front of the house as the officers and their ladies danced on and on, and I can feel over and over the new excitement of Caroline's nearness to me. And there was danger too, I suppose, but I didn't think of that.

The Long Vendetta

The Long Vendetta The Law of the Trigger

The Law of the Trigger Whom Gods Destroy

Whom Gods Destroy Never Say No To A Killer

Never Say No To A Killer A Noose for the Desperado

A Noose for the Desperado Gambling Man

Gambling Man The Last Days of Wolf Garnett

The Last Days of Wolf Garnett The Desperado

The Desperado Boomer

Boomer Death's Sweet Song

Death's Sweet Song The Colonel's Lady

The Colonel's Lady