- Home

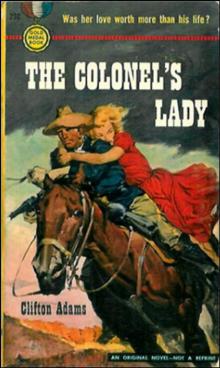

- Clifton Adams

The Colonel's Lady Page 6

The Colonel's Lady Read online

Page 6

We went up the servants' stairway in the deserted part of the house and emerged into a richly carpeted hallway where dark, disapproving family portraits stared down on us from their high places on the wall. Caroline turned a knob, opened a door. The darkness of the room seemed to leap at us and swallow us. I found her in the darkness and there was a new warmness to her mouth, a new eagerness in her body.

I had not known that there was a passion so strong that it could take you up and bend you and twist you and mold you and make you over again in its own shape. I had not known that there was so much animal in man, until that night.

We lit no lamps. There was just Caroline and me, and the rest of the world was darkness. I was glad for the darkness, for I could feel my face burning at my clumsiness. I cursed my hands for shaking, my voice for being paralyzed. But Caroline's heritage was the wisdom of Eve. I was young, and very much in love, and Caroline crooned to me and I could feel the touch of her fingers on my face, and the warmth of her breath on my neck. Her hands went behind my head and pulled me down. And, at last, she calmed me against the softness of herself.

I remember the awakening now. How, after a long while, a whitish moon appeared and sifted pale light through the windows of Caroline's room. I could hear the orchestra still playing below us, and the scuffing sounds of the dancers. And the bright, muffled laughter. All foreign and insignificant and having nothing to do with us.

I looked at Caroline and she was even more beautiful than before. And I loved her even more, if that were possible. I touched her gently and she opened her eyes. In the milky light of the moon I saw that her eyes were wide and filled with terror.

“Matt!”

“I'm here, Caroline.”

The terror dissolved itself. She smiled and reached her white arms up for me and clung to me. “Matt, I'm not afraid any more. Nothing can separate us now. Nothing!”

After that night, of course, I wanted us to be married as soon as possible. It was Caroline who wanted to wait. It was Caroline who always found excuses to set the wedding date ahead—and ahead again, when the time neared. Until at last our energies and senses and emotions became frayed and worn by the war, and finally we decided to wait until I could get a long furlough and we could go back to Sweetbriar for a while. Of course, the furlough never came, for the South was poor in men those days, as it was poor in everything.

But I came back to Caroline's house many times, between campaigns. I watched her beautiful old house change along with the rest of the South and become shabby, and a little ridiculous too, because it was still proud. I watched her father become aged and dead-eyed, and it seemed only a matter of formality two years later when we buried him. All the South seemed to be dying. And Jackson's weary troops marched bloodily up and down Caroline's beautiful valley of the Shenandoah, and the doom she had prophesied had come to pass. And more.

With a great surge and with new life the Union armies began to crush Beauregard and Johnson and even the fierce-eyed, fanatical Jackson, and push deep into the heart of the Confederacy. Even to Sweetbriar, which had seemed to me as permanent as the mountains. Not only Virginia, but the entire South lay dying.

Now, sitting with Caroline again, in Caroline's house, I poured another glass of her fine old oloroso and listened with half a mind to the sounds of Larrymoor coming to life. It was difficult to imagine Caroline in a place like Larrymoor, but it was more difficult to imagine her standing helpless in the midst of the ashes and ruins that were now her valley. Here, at least, she had her paintings and a few pieces of silver and a certain authority and social position to remind her of better things and better times. Not many Southern ladies had as much.

“Do you want to tell me about it, Caroline?” I said.

She looked at me blankly. “About Three Fork Road,” I explained.

She said nothing.

I hadn't expected her to, because that was where she met Weyland, at her fine white house near Three Fork Road, while her South lay drawing its last breath. Gettysburg then was already history, and so were Chickamauga and Chattanooga, and the Wilderness. The lemon-sucking, evangelistic Jackson was dead, and Jube Early, a good man and a good general, tried to take his place, but Phil Sheridan was not to be denied. The year was 1864, and the blue armies marched into the valley.

They took Caroline's beautiful old house, which was now shabby, and established their brigade headquarters there. There were brigathers and colonels and majors, and of course the young and promising captains, and for a little while it must have seemed to Caroline as if the past had been regained. There was gaiety again, and fine uniformed officers and gentlemen. And, of course, the excitement that always goes with military success.

The soldiers this time were dressed in blue, but that was a small matter. And besides, the South was dead.

Three Fork Road was where the plank road to New Market crossed a narrow dirt trail near Martin's Run, and that is where the battle was. If “battle” is the name for it.

I was almost crazy when I learned that Caroline had stayed in the house while the blue armies swept over that particular part of Virginia. When I heard about it I went through the lines, against orders and at night, to find her and bring her out. I remember lying in a wild plum thicket behind the plantation's outbuildings most of that night; then toward dawn I managed to awaken one of Caroline's darkies and got him to tell her where I was. I lay there filthy with the dirt of war, suffering a thousand agonies while I waited. But at last she came. And she said:

“Matt, you shouldn't have come here!”

I don't remember what I said. To look at her was enough for a while.

“Matt, Yankee soldiers are everywhere. They have set up brigade headquarters in the house.”

I said, “I came to take you across the lines, maybe to Richmond. You can stay there with friends until the war's over.”

But she wouldn't leave. She pointed out to me that it would be foolish to leave the house in the hands of soldiers, with no one to look out for things. And she wasn't afraid of being harmed. The Yankees were gentlemen, she said. More gentlemanly than the Johnny Rebs, maybe. The Southern men were all so shabby....

“Do you mean you prefer to remain their prisoner?” I couldn't believe that she was serious.

“I am not a prisoner, Matt. Can't you get that through your head?”

She had changed somehow. I should have guessed, I suppose, but how is a man to think such things when he's in love?

“Matt, how did you get through the Yankee lines?”

“My whole company is through the lines,” I said. “Anyway, beyond their pickets. We've been coming up at nights, a few men at a time, along Martin's Run. Pretty soon we'll have another company up.”

“Where, Matt?”

“Three Fork Road. That's where we're gathering. As soon as we're strong enough we're attacking Sheridan's headquarters in the rear.”

“When, Matt?”

“Two nights from now, at midnight. Jube Early has cavalry and infantry massed to hit Sheridan's left flank at the same time. It would never work, though, unless we disrupt Yankee communications by an attack on their headquarters.”

“Do you mean General Lee is to begin an offensive in the valley?”

“Not exactly. But, by throwing the Union armies into confusion, Lee gains time to regroup his scattered forces around Petersburg.” Then I said, vainly and foolishly, “I'm a captain now, Caroline. Our commander was killed on the James last month.”

“Two nights from now...” she said thoughtfully.

“You've got to come with me, Caroline.”

“I'm safe here, Matt. Safer than I would be trying to get through the Yankee lines.”

She wouldn't come. She said again that it would be foolish to leave all her fine china and silver and linens for the soldiers to ruin or steal.

“Matt, if General Early's attack is a success, this land will be in Confederate hands again.”

“Yes, that's possible.”

&

nbsp; “Then, don't you see, it would be better for me to stay.”

“There was nothing I could say to change your mind,” I said. “You stayed.”

“What?” Caroline said, surprised, and I guessed that I had been speaking my thoughts. Outside, on the Larrymoor parade, the high-pitched cavalry bugle sounded insignificant and lost in the vastness of the desert.

“I was just thinking of something,” I said. “I was thinking of Three Fork Road. I've known for a long time that you told the Yankees we were gathered there, but I didn't know until the other day why you did it, Caroline.”

Her mouth was thin-pressed, determined. She was going to face it out.

“You picked Weyland for some reason,” I said. “He was young, ambitious, came from a good family, probably. Sweetbriar was lost, so there was nothing I could give you. Nothing the South could give you. So you told Weyland about our gathering at Three Fork and he made the charge that wiped my company out. And Early's attack was broken up before it got started.”

She paled slightly, that was all.

“Weyland was a great hero after that,” I went on, “just as you had known he would be. Promotions came fast for him. It would seem that Weyland was a very fortunate man, except for one thing. He was in love with you, Caroline.” The wine I held suddenly became bitter and I put it down. “I just wanted to see if you would deny it,” I said. “That, I guess, is the reason I came to Larrymoor.”

She stood up then, perfectly composed. She smiled suddenly and without warning. “That's not the real reason, Matt,” she said. “You came to Larrymoor because you're still in love with me.”

I had known it all along, and so had she, but still it was a shock hearing the words spoken in the silent room. Then—I don't know how it happened—I was holding her.

She walked to me and my arms went out and closed around her. Her head went back for a moment and I looked into those deep blue eyes of hers, as deep as an ocean, as the sky, and then I crushed my mouth against hers with a viciousness and fury that I had never known before. For a moment I imagined that there was the scent of honeysuckle in the room and that I could hear Captain Fitzhugh Dunham's orchestra playing:

It matters little now, Lorena;

The past is in the eternal past....

“Matt.”

“Yes.”

“It's true. Everything you said is true. But, don't you see, I couldn't stay in Virginia and watch the South die, the South I had loved so much. I couldn't stand it, Matt, I had to get away.”

“Did you have to betray it because you loved it? Did you have to inform against me? Twenty-eight men died that day because of you, Caroline.”

“They would have died anyway, most of them. The entire South was dying. That day or some other day, what difference did it make?” Her hands went behind my head and pulled my face down to hers. “Do you still love me, Matt?”

“I don't know. God help me if I do.”

I kissed her again and she said, “Yes, you love me. Oh, Matt, I'm glad you followed me here. At first I thought you had come to cause trouble, and I hated you for it. But I don't any more. I love you, Matt. I've always loved you.”

“You take strange ways to show it. Why did you marry Weyland if you loved me so much?”

“I explained that, Matt. I had to get away.”

“I would have taken you away.”

“No, you wouldn't have. You would have fought to the bitter end—just the way you did fight to the bitter end.”

“Not quite. I spent six months in the Yankee prison at Fort Delaware because of you, Caroline.”

“I'm sorry, Matt. What else can I say?”

What else could she say? I looked at her, I studied her, and I saw not a particle of regret, not the slightest twinge of conscience for what she had done. To her, it had been the sensible thing, and to Caroline the sensible thing was the only thing.

“Kiss me, Matt,” she murmured. “Hold me close.”

“What about Weyland?” I said bitterly. “You married him. He's your husband. You made a fine hero out of him and got him promotions and then married him because he could offer you things I couldn't. Don't you think you owe him something?”

“Don't talk, Matt.”

“I want to talk. I've got a lot of things to get out of me, and they're not pretty things. What about Weyland?” I felt her shudder against me.

“So that's the way it is....” Somehow I was not surprised. “Tell me, Caroline, was it worth it? Was it worth deserting your country for, and me, this five-room mud house on the edge of God's nowhere?”

“It's better than Virginia,” she said tightly. “Or Alabama.”

“But you hate it just the same, don't you?”

She pressed her forehead against my shoulder and I knew she was crying, although she made no sound and her eyes were dry. “Yes, I hate it. I was going to go back —go anywhere—because I couldn't stand it here any longer. But it's different now that you're here.”

“What difference can I make? I'm not a colonel, not even a lieutenant. I'm just a common trooper.”

“You won't be forever. I know you won't, Matt. I can wait, as long as you're with me.”

It was like talking to a child—a stubborn, persistent, spoiled child who couldn't understand that the world was not made specially for her and for nobody else.

“What do you intend to do?” I said with bitterness. “Send over to headquarters every day and get some 'carpentering' done?”

“Don't talk like that, Matt.”

“How else can I talk? You married Weyland. Not me.”

I wanted to hurt her now. I wanted to hurl her away from me and walk out of the place and never look at her again. But I couldn't do it. I could feel the warmness of her body against me as I held her and the old familiar hunger returned. I could recall a thousand empty nights. For all nights were empty without her. For a moment there were just the two of us, as it had been once before so long ago, with no past and no future. And for that moment I was content.

“Matt.”

“Yes.”

“Kiss me again.”

I kissed her again, bruising her mouth against mine, and only then did I realize how much I had missed her. I don't know how much time passed before I began to feel a difference in the room—before I heard the steady, measured inhaling and exhaling of someone's breathing. I released Caroline and half turned toward the open doorway. Colonel Weyland was standing there.

Chapter Five

I WON'T SOON forget that day. That year-long afternoon that I spent in my bunk waiting for the sky to fall. The troopers of A Company were out on detail when I got back to the barracks building, and I was glad for that because I wanted to be alone. I lay there on my bunk and waited for the end to come, waited for Weyland to do whatever he was going to do, and there wasn't a thing I could do to stop it.

In my mind I kept seeing the Colonel's face as I looked around and saw him standing there. I had never seen so much hate on a face before. Morgan's hate was a pallid, insignificant thing compared to it. Skiborsky's hate was nothing. With Weyland, hate was the man and the rest was nothing. I could still hear his measured breathing as he stood there watching us, and I could see the rage in his colorless eyes. He had said only five words.

“Get to your barracks, trooper.”

That was all. He closed his mouth tightly, as though he were afraid to say any more. He stood there without moving and I walked past him and out of the house. Now all I had to do was wait. Pretty soon the sergeant of the guard would come, and maybe the corporal too, and they would take me away to the little two-celled guardhouse behind the stables and there I would stay until a general court-martial was arranged.

I waited, but the sergeant of the guard didn't come. At last recall sounded and the troopers of A Company came straggling in from whatever details they had been on that afternoon.

“It looks like you've got this army by the tail, Reardon,” Morgan, who had worked in the stables all day

, said dryly.

I tried to grin, but it didn't feel like a grin on my face.

“We're goin' on patrol in the mornin',” Steuber said. “You got your field equipment ready?”

I didn't want to start them wondering any sooner than I had to, so I said I'd better get on it. No one had told me yet that I was under arrest, so I went with the Dutchman and Morgan over to the quartermaster's and drew forage and rations for eight days and two extra bandoleers of carbine ammunition. I expected somebody to be waiting for me when I got back to the barracks, but nobody was there. I made my saddle roll and then went to mess and ate the government dried beans and sowbelly and corn bread, and still nobody tapped me on the shoulder and said come along.

I couldn't understand it. There was no mistaking the hate—almost a madness—I had seen in Weyland's eyes. It didn't make sense that he wouldn't try to do something about it.

After the bugle had sounded for the last time that night, and the barracks were plunged into darkness, I began to wonder if Caroline had somehow calmed him down and explained the whole thing away. God knows how she would do it, but if anybody could manage it, Caroline could.

But common sense told me that wasn't the answer. Weyland wouldn't be calmed and he wouldn't have the thing explained away. The only explanation was that Weyland had, for some reason, decided against a court-martial. He had figured out something better. What could be better than sending me to a government stockade for twenty years, I didn't know. Whatever it was, though, I would learn about it soon enough.

Reveille was at five-thirty the next morning. At six o'clock the fourteen-man patrol with Captain Halan, a young lieutenant named Loveridge, and a Papago Indian scout formed on the parade. Sergeant Skiborsky, as the senior sergeant on the detail, dressed us up and checked our equipment, and at six-fifteen we rode in columns of twos through the gates of Larrymoor and onto the desert.

Nobody tried to stop us.

The Long Vendetta

The Long Vendetta The Law of the Trigger

The Law of the Trigger Whom Gods Destroy

Whom Gods Destroy Never Say No To A Killer

Never Say No To A Killer A Noose for the Desperado

A Noose for the Desperado Gambling Man

Gambling Man The Last Days of Wolf Garnett

The Last Days of Wolf Garnett The Desperado

The Desperado Boomer

Boomer Death's Sweet Song

Death's Sweet Song The Colonel's Lady

The Colonel's Lady